P2p mobile carriers

Abstract

A peer-to-peer marketplace for mobile plans would allow mobile service to be provided with minimal friction and lead to new innovations in the mobile system. In this post, I introduce a new protocol for sharing access to mobile plans with untrusted third-parties.

The protocol uses secret contracts to share U/e/SIM credentials without revealing secrets to a third-party. Due to the way authentication is handled in the mobile system, a third-party is able to authenticate without a secret key, and end-to-end encryption can be applied to prevent owners from reading messages- even with full knowledge of a secret key pair.

To prevent duplicate logins, I introduce a novel method based on fuzzing the state of temporary identity allocation in the visitor location registry. The technique results in cryptographic proofs that can be used to penalize a bad actor if they breach the terms of a contract. Last of all, to protect plans from being abused, I propose a way for owners to impose access restrictions by using trusted computing features found in recent phones.

I know where you live

Every mobile contains a unique hardware ID that enables tracking without the need for a SIM card [imei]. A powered phone is a tracked phone [vlr-update]. A powered phone with a SIM is a tracked subscriber [u/sim-mem]. Want to turn it off? You can’t. To receive calls the network needs to know the base station [hex-call] you connect from (which gets published to a database that is easy to access.) [ss7-tracking][any-time-interrogation][imsi-catcher][aka-tracking]

By now you may be thinking that its better to turn off your phone and be done with it, but modern mobile operating systems are free to specify what the “off” button does [typhoon-box]. So you may think that the phone is off when in reality it’s still in a sketchy standby mode that’s periodically firing up the baseband processor to update its location.

What is a baseband processor, you ask? It is a highly restricted chip that handles almost all interactions with the phone system, and only a handful of companies get to know its full capabilities. While the baseband processor is largely a black box, there are some things we know about them and they’re quite scary.

The chip contains code that allows an operator to manipulate the SIM card, for example, installing applications to the SIM that will persist even after the phone has been formatted [remote-uicc][adpu]. It also allows the police and emergency services to retrieve the exact location via GPS [emergency-location][lawful-interception]. The only conclusion to draw from this is the baseband processor and related SIM card are back doors. Or more precisely, they are implementations of standardised back doors, since what I just described is all part of the mobile protocol suite.

I know what you’re saying

Not one, but multiple weaknesses have been found in phone encryption algorithms, they’ve literally been that bad [breaking-a1-3][snow-weaknesses][kasumi-attack]. Initially an algorithm called “A5/1” was used in 2G networks. The government produced a second version of it and named it “A5/2” - a deliberately weakened algorithm that made it easier to monitor communications. Researchers were able to break it within a month [a5-2], and today we’re all using an algorithm called “KASUMI” instead.

The communications industry has a long history of shutting out security researchers and ignoring problems until its too late. Case in point: look at A5/1. It was never officially published and had to be leaked to be studied [a5-1] because everyone knows that if you keep the details of your system a secret it means the system must be secure</sarcasm>.

Of course, the “security through obscurity” philosophy has been applied to other areas– most obviously in the authentication protocol that every phone on Earth runs. By convention, each operator is allowed to implement their own proprietary algorithms rather than relying on a standardised and battle-tested algorithm [carrier-milenage]. What could go wrong?

By the way, KASUMI still sucks [kasumi-attack][3g-4g-security], and its another reason why people shouldn’t roll their own crypto. What algorithm does the government use for voice encryption? It’s not KASUMI.

You’ll never catch me, I’m the gingerbread man!

Alright, so they may have messed up the whole “crypto” thing, and my phone is now part of the botnet, but what’s the big deal about security, anyhow? My phone still w̲o̲r̲k̲s̲ for making calls, doesn’t it?

Well… not really. Have you ever looked at a city and marvelled at how ugly it looks? That’s kind of what happened to the phone system. It’s layers, upon layers, upon layers of filth. Old infrastructure that has been strewn in place, and left to rot there… exactly why no one can say for sure.

Very little information has survived the GSMA’s standardisation process, but what follows has been pieced together from historical records. The records don’t tell us much, but from what I’ve gathered they speak of a time when networks were smaller, less sophisticated, and easier to maintain.

Back then there were only a handful of operators, and it was generally okay to trust the messages routed between them. Times were different back then, simpler… and the people more naive. They had yet to grow up in a world over-run by ransomware, spam, surveillance, and other threats… and so it was that when a young whipper-snapped called up one sunny day to ask for SS7 access no one even battered an eye lid.

’Nd just like that, a person could stroll in and query the location of any god-damn phone this side of the Mississippi [any-time-interrogation].

Anyone can just register for these things and track people?

No, I’m saying that when you’re ready Neo, you won’t have to. There are already websites that openly give out this info.

My point is that the phone system is systematically flawed. Sure, you can lock down SS7 access- but there are other ways onto the network, and once you’re inside you can pretty much do what you like. The base station centre can be impersonated. The mobile switching centre can be impersonated [msc-impersonation]. Your cell phone can be impersonated [sim-cloning]. Even the base station can be impersonated [stingray].

The core network can’t be trusted. It’s far better to think of a phone as a remote listening and tracking device that’s always on because the phone has those capabilities baked-in [typhoon-box]. It could be listening to you right now and you wouldn’t know it.

It’s a bleak situation and one that’s hard to fix. You would think that a user could at least control their own devices, but that’s not really possible with present phones due to closed-source dependencies. Among many problems: the SIM specification is itself a backdoor that directly supports remote file manipulation [remote-adpu][remote-uicc], and that persists after a reformat. That’s not a 0-day, its literally a standardised feature.

Towards a better phone system

To address the elephant in the room: Only nerds really care about privacy and security anyhow, and the ones who do rarely have the skills needed to make a difference. I’m not saying that’s a bad thing– but one needs to be aware of these factors if they want to change anything.

The reality is, security-based products are hard to sell because their value is only realised in a worse-case scenario. Before then, the customer is left trying to guess which company offers the best defence against a proverbial ghost. And since that’s the case, companies can get away with offering a sub-par solution. It would appear that the main benefit to having good “security” is psychological– at least until a real attack occurs!

What I’m getting at is this: if you want to solve these problems, then you first have to solve a problem people care about, and then you can build privacy and security in as a kind of benevolent trojan horse. Reverse haxing.

So what are some related problems people might care about?

- Pre-paid credit normally expires if more credit hasn’t been bought by a set date. This is a very unethical business practice. How is this even a thing? A customer should be able to keep what they pay for.

- SIM cards are designed to prevent changing carriers and hence are anti-competitive by nature. For a similar reason, pre-paid credit MUST expire in order to prevent a second-hand market for credit from emerging. Less competition = higher prices, and worse options.

- The anti-competitiveness of carriers is extreme in how competing carriers refuse to provide network access to non-customers. A person can be standing right next to a base station and still not have any signal. Surely there is a better way to use these resources?

- In post-paid plans there is often a fixed amount of resources that is included each billing cycle before incurring a penalty. A customer may only need a small amount but because carrier plans only offers a small range of plans at a higher price point, the customer is forced to waste resources every single month. That’s not the best experience.

- Every carrier implements their own billing systems which has generally resulted in a lot of bad billing software. Even having access to accurate usage data is not available on most operators and you only seem to find out when you’ve been penalised hundreds of dollars.

- The phone system is possibly t͟h͟e͟ ͟l͟e͟a͟s͟t͟ ͟s͟e͟c͟u͟r͟e͟ ͟s͟y͟s͟t͟e͟m͟ ͟e͟v͟e͟r͟ ͟b͟u͟i͟l͟t͟. Multiple flaws in its design allow third-parties to spy on calls, track users by their phone numbers, and remotely install spyware. It’s that bad.

Too long; didn’t read? A p2p carrier would save the customer money, prevent their credit from expiring, and even improve mobile coverage. Plus, enhanced privacy and security is always useful. I’ll show later on how a p2p carrier can also support some truly novel use-cases.

Table of contents

- Glossary of key terms

- How authentication is done in mobile networks

- A sketch for a naive protocol

- 3.1. Stage 1 - Carrier authentication via proxy

- 3.2. Stage 2 - Voice encryption setup

- Billing access to a buyer

- Hiding buyer traffic from the seller

- Hiding buyer location details from the VLR

- 6.1. Option 1 - Use someone else as a base station proxy

- 6.2. Option 2 - Reserved

- 6.3. Option 3 - Ignore the VLR for now, we’ll figure this out later

- Preventing non-delivery of services

- 7.1. Option 1 - Micropayment channels

- 7.2. Option 2 - Double-sided deposits

- 7.3. Option 3 - Secret contracts

- Redirecting inbound phone calls

- Preventing unintended communications

- 9.1. SMS messages meant for the seller

- 9.2. Calls meant for the seller

- Technical requirements for a solution

- 10.1. A look at the Android code

- 10.2. Full U/SIM secrets & authentication routines (OR see backup plans)

- 10.2.1. Ideally full knowledge of authentication routines

- 10.3. Plan B) Authentication oracles

- 10.4. Plan C) Public-key cryptography

- 10.5. Plan D) TLS options

- 10.5.2. 5G NG-MASA

- 10.5.3. Higher level protocol encryption

- 10.6. Plan E) A less naive protocol with location checks

- 10.6.1. Proof-of-location

- Carriers banning accounts

- Advanced GSM secret contracts

- 12.1. Low-latency service sharing contract

- 12.2. Detecting contract breach by a seller (algorithm)

- 12.3. Detecting contract breach by a seller (fuzzing)

- 12.4. Detecting contract breach by a seller (sanity test)

- 12.5. Detecting contract breach by a buyer

- 12.6. Detecting contract breach by a buyer (continued)

- 12.7. A contract for faster Internet speed

- 12.8. Virtual micro-carriers

- 12.9. Self-routing programs

- 12.10. Credit that never expires

- Conclusion

- Future work

- References

- Outro

1. Glossary of key terms

IMSI = International mobile subscriber identity. It’s like a unique user ID. In the mobile system you can do many different types of queries by knowing a users IMSI (e.g. retrieving location information.)

IMEI = International mobile equipment identity. It’s like a MAC address for the phone and identifies the make and model. There are few checks on this so its easy to make one up. I’ve listed this here because carriers use IMEIs to ban devices and track customers.

MsC = Mobile switching centre. Kind of like a router in the phone system. It helps to relay calls and SMS to the right nodes in the network, and ensures the correct customer gets billed for a service.

T-IMSI = Temporary international mobile subscriber identity. Acts just like a regular IMSI, but is randomly generated per session. Because the IMSI is used to identify users and is required in some signalling messages, the T-IMSI can be used in place of it as an alias of sorts.

BS = Base station. The base station is the tower that transmits messages to your mobile device on different frequencies. There’s a range of frequencies that are reserved for working out the channels the BS will use with your phone in the future. The way phones use frequencies efficiently is how they achieve the speeds they do!

MS = Mobile station. A mobile device like your phone. The MS talks to the MsC via the BS. Lots and lots of acronyms.

2. How authentication is done in mobile networks

In the 2G/3G/4G/5G networks, authentication follows a challenge-response protocol using symmetric keys to encrypt challenges [aka-protocol]. Both the MS and the MsC have a copy of the same symmetric key and hence are able to encrypt the same challenge.

To authenticate a mobile user, the MsC generates a large random number to use as a challenge and sends it to the mobile user via the base station. The MS encrypts the challenge using the secret key stored in their e/U/SIM card, and returns the response to the MsC.

If the response is a correct encryption of the challenge under the right key, the MsC knows the mobile device must be in possession of the secret key and hence is allowed to join the network. The final stage involves generating a new key pair that is used for encrypting voice calls, SMS, and other commands sent over the air waves.

This is done by inputting the challenge and secret key into the right algorithm – the type of which has been previously negotiated between the MS and MsC. If no algorithm is supported between them, then the MS cannot proceed with the connection.

All the different generation mobile networks follow the same basic protocol for authentication, however more sophisticated changes were made with 3G to allow the mobile device to authenticate the network, and various improvements were made on 4G and 5G to improve privacy.

Different generation networks have standardised algorithms for use with authentication and ciphering, but only ciphering must support specific routines, an operator can do authentication however they like.

3. A sketch for a naive protocol

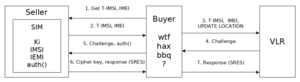

The naive protocol uses the standard authentication protocol, but with a small twist: instead of authenticating directly, a third-party buyer is given authentication responses from a seller which it uses to authenticate.

The following protocol defines how to sell credit to a buyer. The seller is the holder of a SIM secret key who wants to sell credit to a buyer.

3.1. Stage 1 - Carrier authentication via proxy

- Every U/e/SIM contains a secret key associated with a mobile account [3gpp-auth][gsm-crypto][5g-auth][4g-auth][3g-auth][2g-auth][sim-security].

- To sell spare credit, the seller can’t give out this key because it would compromise their account. Fortunately, they don’t have to.

- First, they give the buyer their IMSI number. The buyer can use this to authenticate with the mobile switching center (MsC) [gsm-l3][3gpp-l3].

- The MsC returns the name of a supported authentication function and a random challenge (which is just a large random number.)

- The buyer gives this information to the seller and they use it to calculate a response by passing in the challenge and secret key into the right function.

- The seller gives the response back to the buyer. At this stage the buyer is authenticated but has learned nothing about the secret key.

3.2. Stage 2 - Setup encryption for voice calls

- Calls must be encrypted on the mobile network [new-call]. For privacy and security reasons, a new encryption key is generated each time. To calculate the encryption keys the seller passes the random challenge and secret key into yet another function and returns the result to the buyer [gsm-crypto].

- At this point the buyer is both authenticated and has a ciphering key for voice call encryption, yet knows nothing about the secret key.

- If ever the seller wants to disconnect them, all they have to do is establish a new session with the MsC, and it will automatically disconnect the other party [sim-cloning]. Once this happens the buyer cannot reuse a response to authenticate, and the old T-IMSI and session key will become useless.

- Security can be improved by using temporary IMSI numbers. To protect customers privacy masked IMSI numbers are given out after authentication. These numbers can be used to authenticate [t-imsi][vlr-update].

A good overview can be found at [gsm-101], [gsm-protocol-stack], and [mobile-network-overview] . The remaining sections focuses on the problems that arise from this naive protocol and how to fix them.

4. Billing access to a buyer

After the buyer is authenticated they can do anything on the phone plan. This includes setting up call forwarding and call barring rules; Disabling outgoing and incoming calls; Redirecting incoming calls to malicious numbers; Spamming SMS messages; Internationally roaming; Or setting up a large group conference calls with premium numbers.

Much of this is temporary. You can revert bad rules, lock-down voice mail with pin codes, and apply other restrictions. But is there a better solution? Yes there is, read on to find out.

5. Hiding buyer traffic from the seller

If you’re using a third-parties ciphering key, then they can obviously listen to a call if they’re within radio range. This can be prevented by encrypted the voice call prior to ciphering it, but this means breaking calls to regular phones and what’s the point in that!

One solution to this problem is multi-party computation (MPC).

Multi-party computation allows two or more parties to calculate the result of a function over their own separate inputs without either party learning what the other provided. For our uses, it would allow a buyer to keep the challenge value a secret and let the seller keep their U/e/SIM secret keys away from preying eyes.

Enigma is ideal for this use-case [enigma].

6. Hiding buyer location details from the VLR

Network operators maintain a database called the “visitor location register.” It’s a database that records the cell towers that a device connects from, and the previous value can be queried [vlr-update].

The consequence of this is that buyers will be able to infer the approximate location of where other users last connected from. Likewise, the seller can do the same to other people who use their service, and operator networks may falsely detect this as cloning and ban accounts.

Privacy from the VLR is a difficult problem to solve when the phone system has been built to require it for calling. One of the only papers that tackles this problem directly used in person trading of SIM cards, and that’s hardly a practical option. A better solution still needs to be determined.

6.1. Option 1 - Use someone else as a base station proxy

The naive protocol offers an ideal way to hide a subscribers true location from the VLR. To use it one would find a node to use as a proxy and they would pass information to the base station in range of them while forwarding back responses from the network.

The huge drawback is that now you have to maintain a separate data connection for the proxy and if you use an existing mobile plan the association is still there. Which means it should probably be done over WIFI, in which case, why not just use Skype? It doesn’t make sense.

6.2. Option 2 - Todo

6.3. Option 3 - Ignore the VLR for now, we’ll figure this out later

7. Preventing non-delivery of services

Payment and usage restrictions. Once authenticated, there is no way to restrict how much credit a buyer can use. Likewise, a buyer cannot easily prove that a seller is being dishonest. The question becomes how can anyone trust a seller to provide services if they can’t be verified

7.1. Option 1 - Micropayment channels

Instead of buying all the needed credit outright, a user can send micro-payments over time. E.g. every minute or so. That way, the maximum amount of money that can be lost is limited to a small chunk. The requirements for this to work properly are a locked down service.

International calling, roaming, premium text, and premium calling should be disabled at the account/operator level. If possible, group calls should also be disabled. This is all to ensure that the amount of credit a buyer can use is predictable for billing usage within a payment channel.

7.2. Option 2 - Double-sided deposits

It’s unrealistic to assume that every service can be locked down. So another option is to use something called a “double-sided deposit.”

How this contract works is simple. It creates a joint escrow account between a buyer and seller, where each side deposits an equivalent amount of money. Either side is then able to destroy the group sum of money at any time which creates a strong incentive to work together.

This idea may sound a little extreme at first, but it’s not without precedent in the real world. Collateral is routinely used in real-estate to prevent damage to property, and its common to have previsions in contracts where an early cancellation results in a penalty. The difference is, these contracts only protect one side. The double-sided deposit protects both.

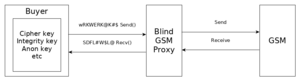

7.3. Option 3 - Se͡c̦̲̺͍̜̀ͅr͉̲̞è̜̝ͅt ̖c̮̝͠o̟͔̫͖͡n͏̖͎̲̞̱t̤̬̦̘̞ŕ̰͚̬͇͔a̯̠͠c̙̘t͕̱̫͝s

Enigma introduced the idea of “secret contracts” [secret-contracts]. What these are, is special programs that encapsulate secret information and allow programs to interact with them through special interfaces without anyone being able to extract the secrets inside.

To illustrate this point in detail, consider the following program:

program(s): return sha256(s + "my ultra secret info");

With a secret contract it’s possible to give out this program to anyone without fear that the string “my ultra secret info” will be extracted. Enigma even makes it possible for programs to receive secrets dynamically, and do other complex computations without fear of leaking information.

Once this concept is understood the original naive protocol can be changed to offer better security:

// Pretend variables marked "secret" use 1337 crypto magic

// that prevents people from seeing them in an active contract.

decentralized_mobile_service_provider():

store_sim_key(secret sim_key):

secret.sim_key = sim_key;

compute_integrity_key(secret challenge):

// For example -- XOR is not how its done on 2/3/4/5g.

secret.integrity_key = secret.sim_key XOR challenge;

compute_cipher_key(secret challenge):

// Again -- not how it's done but as an example.

return sha256("satoshi" + challenge + secret.sim_key);

compute_msg_integrity(secret msg):

if msg != for a standard call:

return

return hmac(msg, secret.integrity_key)

The protocol then becomes this:

- Seller calls store_sim_key(sim_key) and gives T-IMSI to buyer.

- Buyer requests auth against the T-IMSI from the MsC.

- MsC returns challenge to buyer.

- Buyer calls compute_cipher_key(challenge) and uses key to encrypt challenge for an authentication response.

- Response is given back to MsC.

- Buyer calls compute_integrity_key(challenge).

Now the buyer doesn’t need to receive an integrity key. The seller can make it accessible through a secret contract interface that only returns a valid IV for certain message types. Integrity checks are required for 3G, 4G, and 5G [msg-integrity]. Thus, the seller can restrict a buyer with secret contracts and they don’t need to learn a buyers session keys, either.

8. Redirecting inbound phone calls

Incoming calls. In this system calls are being made from someone else’s plan which complicates receiving them back later on. What might work for this is to save a simple voice message that instructs incoming callers to visit a website if they don’t recognize the number. The owner of the plan will have software installed that only accepts calls from their contact list, so they aren’t billed for calls intended for other numbers.

The website previously mentioned could be a simple database that lets a person enter their own phone number + an unknown number to learn which of their friends set up the call. If using an eSIM, these associations should be signed to prevent impersonation.

It’s cool to imagine a calling application using this before a call. Because with that you can create a programmable, virtual switching service on top of a decentralized network. Theoretically, such a service could support any number of rules for forwarding logic, and it would be more flexible and cost-effective than using the built-in operator forwarding.

9. Preventing unintended communications

9.1. SMS messages meant for the seller

SMS messages received in this system will be insecure because buyers will be able to receive SMS messages intended for the seller. Sadly, this is not that much different to how SMS already works [sim-cloning]. Attackers with S7 access can intercept SMS messages easily, and other attacks only serve to make this easier [imsi-catcher].

9.2. Calls meant for the seller

The buyer can also receive calls intended for the seller. The simplest solution is to have a separate plan for receiving personal calls and SMS that isn’t used in the decentralized system.

In practice, eSIM chips support multiple plans, although a program that shares mobile service will need to virtualize most of it. At least with eSIM the account setup will be easy and it won’t become a huge barrier to entry.

It’s possible that secret contracts can be used as an alternative solution to the unintended communications problem. For instance: if incoming calls or SMS messages are delivered using the ciphering key then a custom interface defines who can read them (just like the integrity key).

10. Technical requirements for a solution

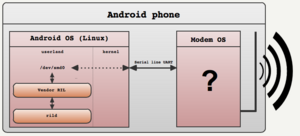

The last problem to solve is undoubtedly the hardest: the sheer technical difficulty of creating a program that implements such a heavily modified GSM protocol.

I have already proposed two such protocols. The first protocol details authentication with a MsC via a sellers challenge response, and the second protocol details a multi-party computation scheme that ensures the two parties cannot learn anything they shouldn’t.

The problem is that both protocols depend critically on being able to access protected portions of the SIM card, as well as being able to send and receive custom messages to the base station (BS) – and all modern phones have been engineered to prevent this! That’s quite the dilemma.

To make things a little easier, I’ll start by assuming that our program will be running on a rooted android device. This shouldn’t be too difficult as there are already lots of one-click methods for rooting android phones. That gets us full access to a phone- but we still need a way to hook API methods in the device. There is a really cool project called “Xposed” that allows custom module hooks for Android API calls [xposed].

10.1. A look at the Android code

[/platform/hardware/ril/+/refs/heads/master/rild/rild.c]

//...

funcs = rilInit(&s_rilEnv, argc, rilArgv);

RLOGD("RIL_Init rilInit completed");

RIL_register(funcs);

//...

Everything starts in the rild.cpp file (RILD = radio interface layer daemon.) This code starts a service designed to handle response messages from the phones radio. The fragment above registers functions for handling responses for the different types of messages.

[/platform/hardware/ril/+/refs/heads/master/libril/ril_commands.h]

{RIL_REQUEST_GET_IMSI, radio::getIMSIForAppResponse},

{RIL_REQUEST_ISIM_AUTHENTICATION, radio::requestIsimAuthenticationResponse},

{RIL_REQUEST_SIM_AUTHENTICATION, radio::requestIccSimAuthenticationResponse},

The RILD allows vendors to write their own libraries for responding to various radio messages [rild]. The required functions are defined in /platform/hardware/ril/+/refs/heads/master/include/telephony/ril.h.

There is also a reference implementation in /platform/hardware/ril/+/refs/heads/master/reference-ril/reference-ril.c. From here on assume that’s what I’m talking about.

[/platform/hardware/ril/+/refs/heads/master/reference-ril/reference-ril.c]

case RIL_REQUEST_GET_IMSI:

p_response = NULL;

err = at_send_command_numeric("AT+CIMI", &p_response);

if (err < 0 || p_response->success == 0) {

RIL_onRequestComplete(t, RIL_E_GENERIC_FAILURE, NULL, 0);

} else {

RIL_onRequestComplete(t, RIL_E_SUCCESS,

p_response->p_intermediates->line, sizeof(char *));

}

at_response_free(p_response);

break;

The MsC may send a message to request the phones T/IMSI number. To access the IMSI the phone uses AT commands to talk to the baseband processor - secret key extract is possible here [baseband-ki-extraction].

The baseband processor runs its own OS that interacts with the phones radio, GPS, and WIFI. It controls access to parts of the SIM. The SIM also has its own operating system that supports applications that can interact with the baseband, and hence the network [java-card][sim-os].

[/platform/frameworks/opt/telephony/+/refs/heads/master/src/java/com/android/internal/telephony/PhoneSubInfoController.java]

public String getIccSimChallengeResponse(int subId, int appType, int authType, String data)

throws RemoteException {

CallPhoneMethodHelper<String> toExecute = (phone)-> {

UiccCard uiccCard = phone.getUiccCard();

if (uiccCard == null) {

loge("getIccSimChallengeResponse() UiccCard is null");

return null;

}

UiccCardApplication uiccApp = uiccCard.getApplicationByType(appType);

if (uiccApp == null) {

loge("getIccSimChallengeResponse() no app with specified type -- " + appType);

return null;

} else {

loge("getIccSimChallengeResponse() found app " + uiccApp.getAid()

+ " specified type -- " + appType);

}

if (authType != UiccCardApplication.AUTH_CONTEXT_EAP_SIM

&& authType != UiccCardApplication.AUTH_CONTEXT_EAP_AKA) {

loge("getIccSimChallengeResponse() unsupported authType: " + authType);

return null;

}

return uiccApp.getIccRecords().getIccSimChallengeResponse(authType, data);

};

return callPhoneMethodWithPermissionCheck(

subId, null, "getIccSimChallengeResponse", toExecute,

(aContext, aSubId, aCallingPackage, aMessage)-> {

enforcePrivilegedPermissionOrCarrierPrivilege(aSubId, aMessage);

return true;

});

}

Heading back towards the official Android API functions you start to see the relevant functions for implementing the challenge-response authentication functions in various phone networks. This code makes a request to RILD -> baseband -> SIM card to retrieve a response to a challenge.

[/platform/frameworks/opt/telephony/+/refs/heads/master/src/java/com/android/internal/telephony/uicc/IccRecords.java]

public String getIccSimChallengeResponse(int authContext, String data) {

if (DBG) log("getIccSimChallengeResponse:");

try {

synchronized(mLock) {

CommandsInterface ci = mCi;

UiccCardApplication parentApp = mParentApp;

if (ci != null && parentApp != null) {

ci.requestIccSimAuthentication(authContext, data,

parentApp.getAid(),

obtainMessage(EVENT_AKA_AUTHENTICATE_DONE));

try {

mLock.wait();

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

loge("getIccSimChallengeResponse: Fail, interrupted"

+ " while trying to request Icc Sim Auth");

return null;

}

} else {

loge( "getIccSimChallengeResponse: "

+ "Fail, ci or parentApp is null");

return null;

}

}

} catch(Exception e) {

loge( "getIccSimChallengeResponse: "

+ "Fail while trying to request Icc Sim Auth");

return null;

}

if (auth_rsp == null) {

loge("getIccSimChallengeResponse: No authentication response");

return null;

}

if (DBG) log("getIccSimChallengeResponse: return auth_rsp");

return android.util.Base64.encodeToString(auth_rsp.payload, android.util.Base64.NO_WRAP);

}

Remember the RILD mentioned earlier? Here is some client code that talks to that server. It will send a request to the radio interface layer daemon to request a response to an authentication challenge message.

[/platform/frameworks/opt/telephony/+/refs/heads/master/src/java/com/android/internal/telephony/RIL.java]

@Override

public void requestIccSimAuthentication(int authContext, String data, String aid,

Message result) {

IRadio radioProxy = getRadioProxy(result);

if (radioProxy != null) {

RILRequest rr = obtainRequest(RIL_REQUEST_SIM_AUTHENTICATION, result,

mRILDefaultWorkSource);

// Do not log function args for privacy

if (RILJ_LOGD) riljLog(rr.serialString() + "> " + requestToString(rr.mRequest));

try {

radioProxy.requestIccSimAuthentication(rr.mSerial,

authContext,

convertNullToEmptyString(data),

convertNullToEmptyString(aid));

} catch (RemoteException | RuntimeException e) {

handleRadioProxyExceptionForRR(rr, "requestIccSimAuthentication", e);

}

}

}

Here is the code in the client for sending requests to the RILD. It’s not very interesting- but the handler for that code is.

[/platform/hardware/ril/+/refs/heads/master/libril/ril_service.cpp]

Return<void> RadioImpl::requestIccSimAuthentication(int32_t serial, int32_t authContext,

const hidl_string& authData, const hidl_string& aid) {

#if VDBG

RLOGD("requestIccSimAuthentication: serial %d", serial);

#endif

**RequestInfo *pRI = android::addRequestToList(serial, mSlotId, RIL_REQUEST_SIM_AUTHENTICATION);**

if (pRI == NULL) {

return Void();

}

RIL_SimAuthentication pf = {};

pf.authContext = authContext;

if (!copyHidlStringToRil(&pf.authData, authData, pRI)) {

return Void();

}

if (!copyHidlStringToRil(&pf.aid, aid, pRI)) {

memsetAndFreeStrings(1, pf.authData);

return Void();

}

**CALL_ONREQUEST(pRI->pCI->requestNumber, &pf, sizeof(pf), pRI, mSlotId);**

memsetAndFreeStrings(2, pf.authData, pf.aid);

return Void();

I’m afraid this is where the trail goes cold. The function CALL_ONREQUEST is a macro that replaces the function name with a call to a vendor-specific library. The vendor thus must supply the function that implements the code to talk to the baseband. Which is fitting really, because they’re the ones who have to manufacture the chip.

So now we know some details about the relevant code in Android for writing hooks. We can use this information to pretend to have a third-parties SIM card by intercepting messages from the radio (more research is required here.) But to implement the full secret contracts there also needs to be a way to extract SIM secret keys, as well as implement the relevant authentication routines for a carrier network.

Here are the options.

10.2. Full U/SIM secrets & authentication routines (OR see backup plans)

Every android phone contains an application processor and a special processor called the “baseband processor.” The application processor is what runs the Android operating system and developer applications. Whereas the baseband processor is for implementing the GSM protocol suite / sending messages back to the radio.

What makes the baseband modem special is that it has full access to the SIM card, meaning that it can read and write anything via a restricted interface. In older android phones this can be exploited to run arbitrary commands on the SIM card by issuing AT commands to the baseband modem [baseband-ki-extraction].

A proof-of-concept on an older Samsung Galaxy will work. Other ideas include using a known vulnerable GSM USB stick.

10.2.1. … Ideally full knowledge of authentication routines

For authentication with the MsC, the GSMA have specified many authentication procedures and key derivation functions that can be used depending on the network (2G, 3G, and so on.)

Unfortunately, while ciphering functions have been standardised [ciphering], the functions to use for authentication are only a suggestion [closed-auth][carrier-milenage][op-specific]. The mobile system is flexible enough to allow each operator to use a different set of algorithms, and some of the standard functions allow an operator to “customise” the algorithm with an operator-specific key (you can think of this like a salt) [op-key].

If every operator were to use a proprietary group of authentication algorithms its not going to be practical to study them. To be determined. The bigger problem is operator-specific keys. How hard are they to extract from a SIM? It might be practical to reverse a few operator keys from the most popular carriers if they only change every few months, but not on a per-SIM basis. And that’s assuming that the chips can be reversed.

Numerous attacks have been found in UUIC U/SIM cards [java-card-attacks], but this is a very specialised area of research [java-card-reverse][oscilloscope].

10.3. Plan B) Authentication oracles

If Option A fails an oracle can be used to compute responses and cipher keys. An oracle would accept a sellers SIM secret and return an authentication response to a buyer.

What’s interesting about this is the oracle wouldn’t need to know enough to authenticate because they would lack a valid IMSI or T-IMSI. Even if the oracle and the buyer were the same person, a T-IMSI would only allow for a one-time use (not an ideal scenario, but its better than nothing.)

[[articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/5.png|articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/5.png]]

The benefit of this scheme is it allows the U/SIM to be used without understanding the full details of the internal algorithms. But critically, it breaks the moment these algorithms vary between U/SIM cards. If there are no other alternatives we are forced to move on to Plan C.

10.3. Plan C) Public-key cryptography

Option C is open if the buyer is calling someone within the same network. In this case, the buyer can just use a recipients public key to encrypt calls. Signal and WhatsApp are all compatible with this method.

10.4. Plan D) TLS options

10.4.1. 5G EAP-TLS

While both standard authentication protocols in 5G (5G AKA and 5G EAP’) transmit challenges without encryption, there is an optional extension called “5G EAP-TLS” which does not [eap-tls][5g-security].

The caveat is that 5G support is still catching up to other technologies, and the EAP-TLS protocol is optional to support [5g-optional-tls]. But there is some hope because EAP-TLS is extremely useful for IoT devices because it provides a way to validate certificates.

10.4.2. 5G NG-MASA

A provisional patent mentions an authentication protocol for 5G called “MASA” [5g-masa]. Similar to EAP-TLS, MASA uses public key cryptography and might be something that is supported on some MsCs.

10.4.3. Higher level protocol encryption

If a secure channel cannot be established during authentication, then there is always the option of enabling encryption at a higher layer in the protocol stack. To understand where this can happen its worthwhile to go over calling in the various networks.

- 2G / GSM uses a circuit-switched network for calls.

- 3G / UMTS switches between 2G for calls and GPRS for data services. GPRS is a packet-switched network that provides IP services for GSM.

- 4G / LTE uses VoLTE (voice over LTE) for calls and falls back to 3G if VoLTE is too busy. 4G is a packet-switched network, so everything is IP-based.

- 5G is still being standardised, and there are a number of options that might be used for calling. For the moment, VoLTE will be compatible. Needless to say, 5G is a packet-switched network.

To start with the obvious: GPRS [voip-gprs], 4G, and 5G can support any regular Internet VOIP application, and end-to-end encryption will prevent packet sniffing between the mobile and the MsC.

Then there is VoLTE. With VoLTE, IPSec can be optionally enabled [4g-link-security] to setup an encrypted tunnel for voice traffic [volte-ipsec]. The IPSec standard uses a protocol called IKE (Internet Key Exchange) for authentication and key exchange [ike-5g].

The way keys are exchanged in IKE is with the Diffie-Hellman-Merkle key exchange algorithm– and guess what that is? Public key cryptography. So even if the owner is sniffing radio packets and sees this exchange they won’t be able to decrypt anything.

10.5. Plan E) A less naive protocol with location checks

The most concerning part about the naive protocol is the potential for the seller to monitor calls made by the buyer. All of the schemes so far have aimed at avoiding this possibility, noting that the original protocol allows a seller to listen in on calls if they’re within radio range.

Most people aren’t going to use a service like this. So if there’s absolutely no other options, Plan E is to somehow ensure there’s enough physical distance between a buyer and seller prior to making a call. Assuming a worse case scenario where a seller knows the approximate location of a buyer after they connect, it would require a huge amount of luck to be within range of a caller during that time.

The United States has over 80,000 cell phone towers and a buyer can use any one of them [tower-count]. Knowing which one to use before a buyer makes a call would enable an attacker to sniff traffic, but there is a higher chance of being hit by a car and dying than correctly guessing a tower. Obviously if an attacker is working with a group they can monitor more towers and increase their odds, but this also raises the cost of an attack.

There is a way to improve the protocol using proof-of-location and secret contracts to solve the millionaires problem. This would help keep out some people and might be a good idea considering there is likely to be a heavy bias around base stations in densely populated areas.

10.5.1. Proof-of-location

A novel startup called Foam Protocol have been working to create a network of radio devices they call “beacons” to allow things to be located in real time [foam-protocol]. Currently this isn’t possible with GPS, as GPS relies on timing delays to determine location, and these are easily spoofed.

Foam Protocol gets around these issues by creating real-time reference points from radio beacons and using them to attest to an objects location. Whats-more, because an object cannot disappear and reappear (duh), an objects path over time also serves as an audit log that automatically collects more signatures of radio beacons over time.

Proof-of-location is useful because it can be used as a safe-guard: if a proof-of-location is generated by both sides and fed into a secret contract the buyer and seller can be sure they’re at least an hours drive apart from each other. The use of random numbers in these proofs forces the buyer and seller to have physical control over at least one valid location.

If a seller manages to somehow fall in the same area as a buyer they are able to be avoid. What this stops is opportunistic attackers that would otherwise be motivated to listen in on calls if it were easy to do. A seller can still posses a valid location and be somewhere else, of course, but that means putting in more effort and getting lucky.

This precaution does not stop attacks, it simply increases the cost for an attacker and makes it (a little) harder to do so. It would be better to use other options than this, or even to sell resources to buy access to a more secure option (e.g. data access with VOIP credit.)

11. Carriers banning accounts

The techniques described in this post represent a new way of providing mobile services. It’s possible that carriers won’t like these ideas and may attempt to ban the people who use them. My thoughts on this are: there are several good reasons why a p2p carrier is beneficial to a carrier:

First of all, the service depends on the carriers underlying infrastructure, so it can’t by definition compete with the carrier. It IS the carrier, albeit a new virtual layer built on top of it, as defined by its users.

It costs the carrier a lot of money to build infrastructure and maintain it. Sometimes this means that carriers have to prioritise the boring parts, rather than giving customers nice features. Since there is no incentive to work on them, there may be less of a reason to buy a plan.

With my approach the carriers get a powerful, new eco-system of developers building products that enhance their value offerings. Such innovations may include better software for faster on-boarding, new features for controlling access to mobile services, even whole new use-cases that have never been thought of before.

The carriers get this for nothing. All they have to do is leave the nerds to do their thing and everyone wins. I’d say that’s a positive outcome.

Another aspect to consider is the the shear difficulty in keeping up with the latest threats in a network that grows bigger every day. There are always new flaws to be discovered, and the hackers just keep coming. How do you stay on top of that in the 21st century?

When it comes to creating an eco-system with a community-driven approach, you’re going to see people empowered to take care of that eco-system – THEIR eco-system – and defend it from threats. Suddenly the mobile system gains an army of security experts writing tools to improve it. None of this is possible without proper incentives.

12. Advanced GSM secret contracts

Anyone who has used a VOIP app before knows how frustrating a bad connection can be. Voice-over-IP often uses UDP for transfer control which results in choppy audio and missed words when packets go missing. Once you start adding in latency it gets worse, and the people start talking on top of each other. VOIP can really suck sometimes.

Despite these issues, we have had some success. We know that if the connection latency is 100 ms or less human-beings perceive it as instantaneous, and anything under a generous 1 second of latency allows for communication without hindrance [ux-response] (the equation for good communication is a little more complicated than that as it also takes into account jitter - a measure of the average variation in time between sending and receiving packets, but close enough.)

With this information in mind there is one terrible limitation to using secret contracts: latency. Currently Enigma uses trusted computing for its secret contracts (and in the future multi-party computing) to divide computations between nodes in a network.

If we’re to use secret contracts to encapsulate integrity proofs, then it will add every communication delay between Enigma nodes communicating these proofs, on top of a voice call. Ultimately, these delays will be so high that it will be impossible to use the system for calling, not to mention that it will require a data channel and we may only have voice minutes available. Clearly this approach needs some work!

So to bring everything together: I will design the final service sharing contract. The new contract will allow voice calls to occur normally, offer greater control over what buyers can access, provide a basic way to enforce quality of service, and allow resources to be split up among multiple buyers (the original contract was limited to only one buyer.)

The new contract will rely on micro-payment channels, secret contracts, trusted computing, VLR fuzzing, disincentives, and insurance.

12.1. Low-latency service sharing contract

- In this secret contract a seller wants to sell access to mobile credit on their plan to an unknown buyer.

- The buyer doesn’t trust the seller to provide this service faithfully and assumes they will attempt to degrade service where ever possible.

- Likewise– the seller doesn’t trust the buyer to pay for it.

The following contract can be used:

- Seller pays a small amount into a contract to register an account. They will use this as a sybil-proof identity in future agreements.

- Seller and Buyer agree on the terms of the exchange such as (credit / price, and expiry time.)

- A new secret contract (SC) is created that houses the agreement code.

- Seller inputs credit amount, SIM key, IMEI, IMSI, and T-IMSI -> SC.

- Buyer calls SC.deposit(credit * price (T)). The contract is now pending buyer acceptance and has a timeout (T.)

- Buyer uses SC.get_auth_response(rand) to login to GSM. Carrier-specific codes are now sent out to check the balance remaining on the account and expiry dates. These messages must be generated through SC as the Buyer doesn’t yet have the integrity key.

- IF the balance == Seller credit AND expiry == Seller expiry, then the buyer calls SC.accept() and the contract proceeds to step 7.

- ELSE, Buyer calls SC.decline(gsm_received_credit_details) which checks the integrity of the input (if it can) using the internal SIM secret to compute an integrity key.

- IF input is a valid message then the Sellers account is BANNED from the network for wasting the Buyers time.

- Buyers deposit bond is fully released.

- IF input is a valid message then the Sellers account is BANNED from the network for wasting the Buyers time.

- IF T elapses without an accept() or decline() from the Buyer, the Buyer receives a small penalty from their deposit bond for wasting the *Sellers** time and the rest of their bond is released.

- When T elapses AND SC has been accepted, the integrity key is released to a trusted processor on Buyers mobile. Running within this processor will be software that restricts the Buyer. Controlling:

- LOCATION UPDATES

- Browser and network activity.

- Service access on GSM

- Billing

- Etc

- If the Buyer wants to update their location they must do the following to avoid race conditions with the Seller:

- Indicate an intention to update the VLR in SC. The SC.state changes to pending and a timer starts, LT. SC releases an integrity stamped update message to Buyer. During this time the secure processor doesn’t allow other messages to be signed.

- Issue a VLR update on the GSM network and obtain the ack values.

- Wait for the timer to elapse.

- Send a GSM status message to check if still connected:

- Processor returns signed_remaining_credit -> RC.

- If not OR LT timeout, processor restricts the Buyers access and buyer calls SC.finish(RC). SC won’t allow re-auth from Buyer in this state, either. The channel has now closed.

- The SC.state changes to finished.

- ELSE call SC.continue(VLR proof value, RC).

- Return failure if VLR proof value has a bad integrity value and isn’t a valid response using the old T-IMSI.

- Change SC.state to “locked-in.”

- When the Buyer is done using the service, they may call SC.finish(RC) to close the channel. SC.state changes to finished.

[[articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/6.png|articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/6.png]]

12.2. Detecting contract breach by a seller (algorithm)

In the event of a network failure the buyer needs to know if the seller is to blame for it. In fact, there should be a mechanism that acts as a deterrence against the seller using their own service.

What I propose to achieve this is a novel method that allows the state of temporary identity allocations in a VLR to be fuzzed. Before I introduce this protocol it is necessary to understand exactly how temporary identities are allocated by the VLR, including every edge case.

From here on I will use ‘TID’ to refer to these values:

- 2G TID = [t-imsi].

- 3G TID = [t-imsi] for voice, and [p-tmsi].

- 4G TID = [guti].

- 5G TID = [5g-guti].

Behaviour of TID allocation:

- Option A) The mobile device authenticates with the MsC and the VLR returns a new TID. To complete this protocol the MS acknowledges the TID. The state changes to { NEW: { T: TID, I: IMSI } } in the VLR.

- Option B) The same as Option A, but the MS doesn’t acknowledge the new TID. The state changes to { OLD: { T: self.NEW.T, I: self.NEW.I }, NEW: { T: TID, I: IMSI } }. Authentication accepts both TIDs.

Key aspects of session management:

- Premise 1: A subscriber can only exist in one VLR at the same time. If a subscriber roams to a new VLR their old records are deleted [premise-1].

- Premise 2: If a subscriber has an active session with an MsC and another entity tries to authenticate as the same subscriber, the first session will be terminated and result in errors [sim-cloning].

- Premise 3: A location update without successful authentication DOES NOT result in a change to TID state. Authentication is required [location-updates][tid-allocation-4g][tid-allocation].

- Premise 4: TIDs must be allocated after every new location update [tid-allocation], but in practice not all networks properly follow this [tmsi-implementation]. TIDs may also be deleted or change randomly throughout a session.

- Premise 5: VLR information may become corrupt or expire if too old.

- Premise 6: Different networks use different names for temporary identities. Refer to the following list for each network.

Putting it all together:

Auditor attempts to issue location update with latest buyer TID (BT).

- If MsC sends back an identity request the Seller must have logged in from a new location or acknowledged a new TID. Penalise Seller.

{ NEW != BT }- If it asks for auth, BT is still a valid a TID.

Auditor authenticates with Sellers IMSI and retrieves a new TID (T1) which they don’t acknowledge.

{ NEW = X OLD = Y }Auditor attempts to issue a location update with BT as the TID.

- If MsC sends back an identity request we can conclude Y == BT which means the Seller attempted to use an incomplete location update to evade detection. Penalise Seller.

X == ? (seller overwritten value) Y == BT

- If we’re prompted for authentication it must mean that X == BT, hence no changes have taken place after the Auditor last checked. Buyer now changes BT in secret contract to T1. T1 is the most recent value.

X == BT (buyer latest value) Y == T1

Before the buyer accepts the secret contract for the first time they authenticate with the MsC using the TID provided by the seller. Should the sellers information be correct, the outcome from this process will be a new TID which the buyer saves to the contract.

The contract, and the buyers trusted processor control when the buyer can issue a location update. The rules state that the buyer has a set amount of time to issue an update, and to proceed with the contract, they must provide proof that the MsC accepted an update by providing a location update accepted message signed by a valid integrity key.

Such a message may include a new TID, from which we can infer what the TID allocation state in the buyers local VLR should be. If the buyer is unable to provide such a proof, they must end the contract by committing their current credit usage. We cannot deduce here if a failure was the result of a malicious buyer, seller, or some kind of network failure, due to the presence of race conditions. Multiple parties can issue location updates here at the same time so penalty breaches shouldn’t assigned.

In order to ensure that the buyers update has gone through, they simply issue an update, wait for a response, and decide on an outcome after a countdown X, reaches zero. If anything goes wrong before X expires, the buyer may gracefully end the contract, paying only for the credit they’ve used. No damages can be awarded to the buyer or seller in the event of a failed update due to the presence of race conditions.

Thus, a seller is only able to disrupt service by anticipating the start of the X countdown- and if they fail to guess this correctly, the buyer will have proof of a breach and can penalise them via the fuzzing protocol.

12.3. Detecting contract breach by a seller (fuzzing)

Once the new TID has been locked-in, we can infer interference by carefully examining the state of the buyers local VLR. First, we know that manual changes to the TIDs can only occur via a successful authentication and we’re able to control when that occurs for the buyer. Thus, we already know what state they should be in.

Next, we know that two sessions for the same subscriber aren’t possible. So if a buyer is suddenly disconnected it may be the result of a malicious seller or a network failure. In this case, an agent (buyer or untrusted third-party) can immediately start the fuzzing protocol.

An agent running the fuzzing protocol starts by checking if there is still a record of the buyers latest TID in (any) VLR. If there isn’t, their local VLR can no longer determine what IMSI it belongs to and thus will issue an identity request back to the agent. If that occurs we can infer the seller has interfered because only the seller has the keys needed to authenticate outside the secret contract and without knowing the latest TID.

(Note to self: It may be that the fuzzing protocol should only be run against the same VLR that last stored the latest TID. I need to confirm this.)

To differentiate this from a TID expiry, the buyer is required to issue periodic location updates. Since all incoming GSM messages to the buyer are encrypted and must pass through their secure processor for deciphering, the processor is able to track any changes that might occur to the TID, along with any sessions that might have ended uncleanly.

To prevent the possibility of a buyer trying to hide TID changes and use them to falsely accusing a seller of interference, the seller blame process also requires a signed message from the buyers trusted processor attesting that their current TID is still valid. This handles any weird edge-cases that might occur during network failures.

Assuming that there was no previous identification request, the VLR will acknowledge the current TID by issuing an authentication request. The question now becomes how do we determine the exact state in the VLR? We already know that if a TID reallocation isn’t acknowledge the VLR keeps a mapping of the old value = IMSI and the new value = IMSI.

New = ? Old = ?

Thus, if the seller has not interfered there should be no value attached to “old”, and new should point to the latest TID of the buyer. The exact state mapping can be deduced by authenticating without acknowledging the new TID reallocation, followed by a new session with a location update using the buyers latest TID.

Old = null New = Buyer TID

If the old TID was already equivalent to the buyers latest TID prior to authentication, then generating a new TID and not acknowledging it will result in the VLR setting the old TID to the value stored under the current new TID, and then setting the current new TID to a random TID. Thus, the buyers latest TID will get “bumped” off the VLR if a seller had already tried this, and we’re able to detect this by checking the result of a subsequent location update attempt (does it still acknowledge the TID or not.)

Before: > Old = Buyer TID > New = ? (seller compromised)

After: > Old = ? (seller compromised) > New = Latest TID

Fuzzing in this way is very efficient because step 1 only has to run if the buyer has been disconnected, and it determines if a seller has authenticated in another location area in the same step. The following steps check if a seller is authenticating in the same location area as the buyer.

Potential TID changes need to be tracked throughout a session by the buyers trusted processor, but as long as proof of these packets is fairly reliable, the fuzzing protocol doesn’t require much trust. An additional node could always be appointed to record incoming GSM packets for audits. The full protocol can provide proof-of-interference by integrity-stamped messages, and is able to be run by a third-party using secret contracts.

Todo: There may be a better way to detect TID changes for a buyer.

What’s interesting about this protocol is it appears to be resistant to race conditions in that any attempt by a seller to disrupt fuzzing only results in the protocol returning faster (since the buyers TID will be bumped-off.) This is a useful property to have because the VLR contains logic that ignores subsequent location updates which could be exploited.

Another useful property of this protocol is any agent (other than the seller) can run it with minimal trust and use the messages returned to prove the outcome (they contain proof-of-integrity.) Should the seller believe that these messages are in error (perhaps by operator interference or a broken trusted processor) they may deffer to an auditor to run the protocol.

12.4. Detecting contract breach by a seller (sanity test)

It’s possible that a VLR implementation will not be compatible with the fuzzing protocol. For example, if it were to allow more than two TIDs to be valid for a single IMSI. To detect this case: a dry run of the fuzzing protocol should be run prior to accepting the secret contract. The buyer can then decide whether to proceed without penalty breaches for a seller.

It should be noted that regardless of what occurs, both sides are always free to close out their channels and pay what they owe. Should a sellers service become unusable or end prematurely, the buyer can always close out their channel and contract with a new seller.

12.5. Detecting contract breach by a buyer

In the new version of the sharing contract, integrity and ciphering keys have been moved from the secret contract into a secure section of the buyers mobile device. On the latest phones from Samsung there is a feature called “Samsung Knox” for running secret code on an untrusted host [knox].

It’s unknown how secure this is, so what I propose is a DAO can be used for insurance or bounties. In the event that a buyer consumes more credit than expected, a sellers contract will be terminated and any outstanding balance minus the buyers escrow can be paid out via the insurance DAO.

A fee can be paid from a sharing contract into the DAO to be eligible for insurance. After the buyer accepts the contract, and integrity and cipher keys have been transferred into their trusted processor, they may manage to extract them and bypass credit limits. Fortunately, even if a % of users manage to extract keys and exploit the system, contracts remain viable as long as the DAO can cover losses.

It should be noted that in order to claim insurance a DAO appointed auditor would need to have checked the initial credit balance for a seller. Otherwise a seller could contract with themselves and claim they just lost millions in credit. This would only need to be done if the contract is insured and the seller is claiming to posses new resource. After that, they can provision their resources any way they like without needing a new audit. There may be a way around this requirement.

12.6. Detecting contract breach by a buyer (continued)

While trusted computing and insurance offer good safe guards against abuse, its still recommended that sellers take the time to lock-down their plans by disabling any obvious features of abuse (e.g. premium SMS / calls, group calls / roaming, international, etc.)

The risk of abuse is less when a plans resources are being sold to the same buyer. Because by convention, the buyer must be able to fully pay for the resources so their escrow will always have enough to cover the cost of service. It’s only when resources start to be divided between different buyers that you run into problems.

Consider a seller provisioning resources to multiple buyers. Each buyer is only going to pay for the resources they’re interested in. So a malicious buyer who is able to bypass a secure processor can consume resources reserved for other buyers. And who should pay the cost if insurance wasn’t included in the contract? The other buyers haven’t done anything wrong.

One safe-guard to put in place might be to have GSM I/O go through a randomly selected node that acts as a packet notary. These notaries will only relay ciphered GSM packets if the first N bytes don’t match a certain pattern. They will also record the meta-data for ciphered responses from the network which can be audited to check for TID reallocation. Notaries don’t need to see a full conversation, only a small portion of each packet, and they would also hide a buyers location from the VLR as a cool bonus.

The following sections list a few contract examples

12.7. A contract for faster Internet speed

Within a mobile network the maximum Internet speed that a customer can achieve is capped to prevent interfering with other customers. The only way to increase speeds is to buy a better data plan (if any are available) or purchase additional plans.

With a second plan the theoretical maximum resources available for downloads + uploads is doubled, but within the context of the web, most web servers (and most browsers for that matter) are only built to stream data down a single connection. Consequently, two mobile plans might allow a page with lots of elements to load faster but it won’t increase the speeds down a single TCP stream.

There is an exception though, and most people will recognise it: [torrents].

Since torrents split up files into chunks, each chunk can be streamed down a different TCP connection over both mobile plans. So in this scenario its very easy to utilise all resources. But are most people willing to pay twice as much, for twice the speed in such a niche scenario? Probably not.

Fortunately, the service sharing contract offers the ideal primitive to build something for this niche. Consider a scenario where a person has unneeded data left on their plan and they would really like a faster connection right now. In this case, they can form a contract with a group of sellers to buy immediate access to their service plans in exchange for the buyers having access to their plan at some point in the future.

[[articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/7.png|articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/7.png]]

The service sharing contract allows bandwidth and other resources to be aggressively leveraged for a faster connection.

It’s quite interesting to note that the seller can define precise limits on speed in the buyers trusted processor. Meaning that plans become more fungible and can be created on demand to suite the needs of a buyer.

Note: multiple phones and good networking knowledge would be provided to utilise this contract, but I can imagine an app that would make this easier.

12.8. Virtual micro-carriers

There are many unique features that differ between mobile plans. For instance, some plans may cater to businesses more than others by offering cheap fax service. While other plans may be more suited to teenagers.

The service sharing contract turns every potential plan into its own virtual micro-carrier. These micro-carriers are free to design entirely new mobile or Internet experiences through the use of trusted code. Many new services can be combined into a single package, complete with its own access rules, and sold on an open market.

[[articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/8.png|articles/p2p_mobile_carriers/8.png]]

One exciting consequence of micro-carriers is the ability to create backwards compatible improvements to the mobile system. These improvements might include better payment experiences, or even novel voice services. The service sharing contract makes any improvement liquid commodities that can be traded or used by machines.

12.9. Self-routing programs

One very strange program that can be built with micro-carriers, is what you might call a “self-routing program.” A self-routing program maintains a token balance inside a contract and uses it to buy data service from a decentralized marketplace.

The program would ensure that it always has a way to access the mobile Internet and buys enough access to trusted mobile processors to be able to keep itself running (these devices may not have any credit outside of what the program brings.)

By decoupling the mobile plan from the host machine, a program is able to control the level of connectivity it has to the Internet. It may not seem like it at first inspection, but this is very different to renting servers. A server is a fixed target and its Internet access cannot be transferred to another host if it goes down, hence p2p network services lack that level of control.

A self-routing program can use the same plans on different devices, and move between them as they go offline. In the future, a self-routing program may turn out to be a better way to create “unstoppable services” since Internet access is bought directly rather than relying on other people to maintain routing infrastructure.

12.10. Credit that never expires

Selling temporary access to a service plan can be precisely controlled to specify properties like speed, data usage, and so on. This level of fine-grained control allows service plans to become liquid commodities, and once that happens, they will be able to be tokenized and traded freely.

Implementing credit that never expires from this becomes as easy as selling remaining resources for stable tokens and then buying them back when they’re needed. No more expiry, you actually get what you pay for.

What other contracts are possible? Could a contract for lower latency be created? That would be useful for gaming.

13. Conclusion

The AKA protocol in the mobile system can be extended to support shared access to a mobile plan with an untrusted third-party.

A simple protocol that relays authentication messages between a remote mobile device and an MsC is an example, but one that is vulnerable to packet sniffing, session disruption, and abuse.

To defeat packet sniffing, a number of options were proposed. They include: variations on AKA authentication that support public key cryptography; End-to-end encryption at the application level, or between users in the same system; VOIP applications; SIM authentication oracles; Secret contracts; And lastly, physical distance to make packet sniffing more difficult.

To prevent session disruption a novel technique can be used to detect bad behaviour. Once detected, an offending party can be punished through a smart contract. Abuse against a plan is prevented by applying access controls and enforcing them with trusted computing.

14. Future work

Many questions still remain about how widespread certain practises are in the mobile system. This information will be extremely to have for development purposes. But unfortunately, it can only be found by manually checking a carrier to see how their networks work.

More experiments need to be done to confirm the practically of these solutions. I plan to buy some more card readers, SIM cards, embedded mobile models, old phones, and so on, to get the data I need.

There is still a lot of work ahead, but I believe even if a full system is never built the resulting research and code produced will be valuable for other purposes. If a prototype is built the sky is the limit.

A peer-to-peer network of mobile plans would be an excellent way to bootstrap a mesh network, too. It’s cool to think about what an alternative web medium could look like in such a network. Maybe [Scuttlebutt] would be a good model? There are lots of services that could be built with this.

15. References

[imei] Digital cellular telecommunications system (Phase 2+); Network architecture (GSM 03.02), page 9, https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_gts/03/0302/05.01.00_60/gsmts_0302v050100p.pdf

[vlr-update] Security in the GSM system, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b0c8/493e0c6b6e5e08d870a1b318401236e07e82.pdf

[u/sim-mem] SIM/USIM cards, http://cedric.cnam.fr/~bouzefra/cours/CartesSIM_Fichiers_Anglais.pdf

[ss7-tracking] SS7: Locate. Track. Manipulate, https://www.slideshare.net/3G4GLtd/ss7-locate-track-manipulate-75689546

[any-time-interrogation] User Location Tracking Attacks for LTE Networks Using the Interworking Functionality, http://dl.ifip.org/db/conf/networking/networking2016/1570236202.pdf

[imsi-catcher] The Messenger Shoots Back: Network Operator Based IMSI Catcher Detection, https://www.sba-research.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/providerICdetection.pdf

[typhoon-box] Drone Warfare in Waziristan and the New Military Humanism, page 4, https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdfplus/10.1086/701022

[aka-tracking] New Privacy Threat on 3G, 4G, and Upcoming 5G AKA Protocols, https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/1175.pdf

[remote-uicc] 3GPP TSG SA WG3 Security – S3#30 , ftp://www.3gpp.org/tsg_sa/WG3_Security/TSGS3_30_Povoa/Docs/PDF/S3-030534.pdf

[lawful-interception] GSM and 3G Security, http://www.blackhat.com/presentations/bh-asia-01/gadiax.ppt

[emergency-location] ETSI TR 103 393 V1.1.1 (2016-03), page 12, https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_tr/103300_103399/103393/01.01.01_60/tr_103393v010101p.pdf

[breaking-a1-3] Instant Ciphertext-Only Cryptanalysis of GSM Encrypted Communication, https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-540-45146-4_35

[snow-weaknesses] Selected Areas in Cryptography: 9th Annual International Workshop, page 48

[kasumi-attack] A Practical-Time Related-Key Attack on the KASUMI Cryptosystem Used in GSM and 3G Telephonym, https://www.iacr.org/archive/crypto2010/62230387/62230387.pdf

[a5-2] Ian Goldberg, David Wagner, Lucky Green. The (Real-Time) Cryptanalysis of A5/2. Rump session of Crypto’99, 1999.

[a5-1] Another Attack on A5/1, https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7b90/26428bf21b3b3c2208f50187a4922f90b0d8.pdf

[carrier-milenage] TS 135 205 - V13.0.0 - Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS); LTE; 3G Security; Specification of the MILENAGE algorithm set: An example algorithm set for the 3GPP authentication and key generation functions f1, f1, f2, f3, f4, f5 and f5; Document 1: General (3GPP TS 35.205 version 13.0.0 Release 13), page 5, https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/135200_135299/135205/13.00.00_60/ts_135205v130000p.pdf

[sim-cloning] SIM cards: attack of the clones, https://www.kaspersky.com.au/blog/sim-card-history-clone-wars/11091/

[stingray] LTE security, protocol exploits and location tracking experimentation with low-cost software radio , https://arxiv.org/abs/1607.05171

[msc-impersonation] User Location Tracking Attacks for LTE Networks Using the Interworking Functionality, http://dl.ifip.org/db/conf/networking/networking2016/1570236202.pdf

[remote-adpu] Smart cards; Remote APDU structure for UICC based applications (Release 6, https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/102200_102299/102226/06.09.00_60/ts_102226v060900p.pdf

[aka-protocol] Security analysis and enhancements of 3GPP authentication and key agreement protocol, https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/1413239

[gsm-crypto] MOBILE PHONE SECURITY SPECIALIZING IN GSM, UMTS, AND LTE NETWORKS, http://sdsu-dspace.calstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10211.3/123895/Lewis_sdsu_0220N_10457.pdf

[2g-auth] Authentication and related threats in 2g/3g/4g networks, https://coinsrs.no/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/metochi2016-Borgaonkar-authentication-in-2g3g4g-networks.pdf

[3g-auth] 3G Networks By Sumit Kasera, Nishit Narang, page 449

[5g-auth] A Formal Analysis of 5G Authentication, https://arxiv.org/pdf/1806.10360.pdf

[4g-auth] AUTHENTICATION AND KEY AGREEMENT IN 3GPP NETWORKS, https://airccj.org/CSCP/vol5/csit54413.pdf

[3gpp-auth] Confidentiality Algorithms, http://www.3gpp.org/specifications/60-confidentiality-algorithms

[new-call] Module Interfaces (GSM Originating Call), https://www.eventhelix.com/gsm/originating-call/gsm-originating-call-cell-mobile-network-fixed-network-level-view.pdf

[t-imsi] ETSI TS 101 347 V7.8.0 (2001-09), (page 31), https://www.etsi.org/deliver/etsi_ts/101300_101399/101347/07.08.00_60/ts_101347v070800p.pdf

[gsm-101] https://www.slideshare.net/gprsiva/gsm-presentation-shaikot

[gsm-protocol-stack] http://archive.hack.lu/2012/Fuzzing_The_GSM_Protocol_Stack_-_Sebastien_Dudek_Guillaume_Delugre.pdf

[enigma] Enigma: Decentralized Computation Platform with Guaranteed Privacy, https://enigma.co/enigma_full.pdf

[secret-contracts] Defining Secret Contracts, https://blog.enigma.co/defining-secret-contracts-f40ddee67ef2

[msg-integrity] From GSM to LTE-Advanced Pro and 5G: An Introduction to Mobile Networks and Mobile Broadband, https://books.google.com.au/books?id=AEozDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT269&lpg=PT269

[xposed] Development tutorial, https://github.com/rovo89/XposedBridge/wiki/Development-tutorial

[rild] Radio Layer Interface, https://wladimir-tm4pda.github.io/porting/telephony.html

[baseband-ki-extraction] Attacking the Baseband Modem of Mobile Phones to Breach the Users’ Privacy and Network Security, http://ccdcoe.eu/uploads/2018/10/Art-16-Attacking-the-Baseband-Modem-of-Breach-the-Users-Privacy-and-Network-Security.pdf

[java-card] Java Card, https://docs.oracle.com/en/java/javacard/3.1/guide/index.html

[sim-os] [DEFCON 21] The Secret Life of SIM Cards, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WMII5G98AdM

[op-key] 3GPP TR 35.934, http://www.arib.or.jp/english/html/overview/doc/STD-T63V12_00/5_Appendix/Rel12/35/35934-c00.pdf

[closed-auth] Everyday Cryptography: Fundamental Principles and Applications, page 503