Timechain

Author commentary[edit | edit source]

We first published our work on "timechains" on Saturday, 20 June 2015 -- as of 2025 that's more than 10 years ago. The timechains paper described how sequential hashing could be used to delay the release of time-lock encrypted ECDSA keys. The neat thing about this was these keys were compatible with the blockchain systems at the time. So you could create smart contract schemes that needed time-locked transactions using a timechain -- at least that was the idea.

Timechains might have been the first mention of using a deterministic, lengthy, sequential function to delay an event in a blockchain context. The name for such functions ended up becoming known as "verifiable delay functions." So where are VDFs at today? Well, last I checked they were still grappling with the very same issues this paper raises: which is that its very hard to design a VDF whose execution will remain consistent across a wide number of platforms. VDFs have found their way into some blockchain protocols. The one that stands out to me is Filecoins use of VDFs to prove that information remains stored over time.

I'm unsure if Filecoin still uses VDFs; if its efficient; or if they've managed to solve the issues with VDFs.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

By Matthew Roberts and Elías Snær Einarsson[edit | edit source]

Update: April 20, 2017 - See “Turning back the clock on timechains - a follow-up” for a discussion on security.

Historically companies and individuals have struggled to uphold adequate security practices when it comes to the handling and storing of cryptocurrencies and this can be seen in the numerous hacks that have plagued this industry.

Probably almost every large Bitcoin exchange and wallet provider have seen at least one major security incident which either lead to (or could have lead to) the loss of customer’s funds. The problem at hand is actually very simple and comes down to one basic issue: the need to keep ECDSA private keys around for signing withdrawals.

Example 1[edit | edit source]

Imagine you’re a currency exchange for cryptocurrencies. To be able to credit customer’s accounts you generate Bitcoin addresses on the fly and associate them with your customer’s accounts. Now, when your system detects > 6 confirmations for a new transaction you credit the appropriate account.

But what about withdrawals? You need to be able to sign transactions to move coins from your service so you also have to keep a key around on your server. What happens to the key if the server gets hacked? You say you don’t store all your customer’s money in the “hot wallet” but I’m pretty sure people are still going to be pissed if only 10% of their money is lost. And I’ll give you a few more examples of this problem.

Example 2[edit | edit source]

You’re an escrow service that accepts customer’s alt-coins and returns them back to one or more parties based on some arbitrary condition. If you’re like most escrow services out there you’re using 2 of 3 multi-signature to do this where participants can cooperate if the escrow service disappears but this opens up a potential extortion scenario: > Give me a cut of your money sucka, or I don’t sign!

And now for the final example that we suspect people will be the most interested in: smart contracts.

Example 3:[edit | edit source]

You’re working on a hot new startup that’s solving financial problems with smart contracts. Your solution is practically perfect. You have a refund protocol in place if participants try to cheat and maybe even a way to punish the cheaters - the specifics here don’t really matter. Unfortunately, you also have no clue about TX malleability so your design breaks when the output that the refund spends is mutated.

Maybe you’re holding onto the hope that developers will eventually fix Bitcoin, but major changes to Bitcoin (even soft forks) are a big deal so innovation moves slowly. And on top of that alt-coins are probably never going to be completely up to date. We know alt-coins that still haven’t patched issues that were fixed in 2012 so to summarize: most smart contracts are completely fucked until the malleability problem is fixed.

But what would you say if we told you all these problems and more could be solved with a new data structure based on time-lock encryption And that this data structure could be used with Bitcoin today - requiring no additional changes - not even a soft fork or non-standard transactions And further: that this data structure was deterministic - it’s basic behaviour could not be changed from the time it existed to the time it ended?

You would probably think we were lying, right? But you would be wrong. FOR ONE EASY PAYMENT OF … We are joking but do keep reading, we’re really not trying to sell anything here although I have a feeling certain super computing clusters are really going to appreciate this post.

Time-lock encryption[edit | edit source]

Our design starts with something called “time-lock encryption” which is a secure way to send messages to the future. The basic idea behind time-lock encryption is that you start with some random text and then repeatedly apply some computable function to scramble the input. The output of this function then becomes the input to the next function and you keep applying it for however long you want your time-lock to last.

When you’re done with this process, the final key becomes the key that you use to time-lock encrypt information. Now encrypt something and throw away that key so you’re only left with the random input you started with and now in order to decrypt your message, you would have to repeat every lengthy computation used to produce the time-locked key.

import hashlib, time

def timelock(duration, iv):

#Starting time.

last_run = time.time()

#Generate time-lock encryption key.

elapsed = int(time.time() - last_run)

key = hashlib.sha256(iv).digest()

while elapsed < duration:

key = hashlib.sha256(key).digest()

elapsed = int(time.time() - last_run)

#Time-lock encrypted key.

return key

#How long should the time-lock last?

duration = 10

#Starting text or "IV."

iv = b"Did you know shinigami love apples?"

#Lets do this.

key = timelock(duration, iv)

#Some function here to use that key for an encryption algorithm.

#I'll show you how to do this later on.

plaintext = "secret stuff"

cipher = make_aes_cipher(key)

ciphertext = encrypt(plaintext, cipher)

"""

.:. Ciphertext is now "time-locked" discarding the key forces the recipient of the

ciphertext to have to repeat the same process used to generate the key.

Pretty cool, right?

"""

The function used to garble text is called a cryptographic hash function. Its most important property in this context is that it’s one-way - you can’t reverse a cryptographic hash to produce the input used to generate the hash without using a brute force attack which isn’t feasible on large key spaces (so lets just say a good hash function is secure.)

When you’ve done the computations necessary to generate the final value you can use this value to encrypt a private key used in a public key scheme (like RSA.) That way you don’t need to produce a new key every time you want to time-lock something and everyone is free to use the public key.

Introducing the timechain[edit | edit source]

Ordinary time-lock encryption is useful if you know in advance what time frame you want to encrypt something (and obviously if you have the resources to be able to do it), but what if you don’t? What if you want to be able to provide a secure time-locking service to other people so they can encrypt sensitive information to be made available at a future date?

The timechain solves that problem. Using the timechain it is possible to produce information that can only be read after certain times. In its most basic form the timechain is a chain of time-lock encrypted RSA keys at 5 minute intervals and the chain itself can be generated in parallel by using a super computer (e.g. a GPU cluster.)

Stitching parallel keys into a single chain with encryption[edit | edit source]

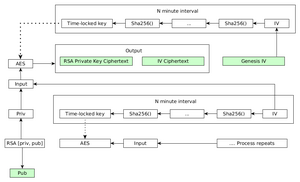

In the simple example we started with - a time-lock of 1 year would be roughly equivalent to 1 year of computation. If it takes a whole year to generate a single timechain this concept wouldn’t be very useful. Fortunately this problem can be solved by generating separate N minute keys on a GPU cluster and then stitching them all together with standard symmetric encryption (AES) to form a chain of 5 minute RSA public keys.

After releasing the starting IV to the chain (called the genesis IV), the chain must then be broken in serial, however the exact time needed to break the chain will fluctuate based on available computing power as well as advances in sha256 performance - a problem we address later in the paper.

import time

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto import Random

from Crypto.Cipher import PKCS1_OAEP

from Crypto.PublicKey import RSA

def make_aes_cipher(key):

return AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CFB)

def encrypt(plaintext, cipher):

return cipher.encrypt(plaintext)

"""

These are abstract functions defined previously or

for demonstration purposes only.

"""

def timelock(duration, iv):

return iv

def publish_timechain(genesis, timechain, genesis_time):

return None

"""

Generate starting IVs for parallel keys.

These need to be distributed to individual processors.

"""

ivs = []

key_no = int(1 * 365 * 24 * 60 / 5)

for i in range(0, key_no):

iv = Random.new().read(32)

ivs.append(iv)

"""

Generate individual time-locked keys.

(Image this is done in parallel because I'm lazy.)

"""

keys = []

duration = 5 * 60

for i in range(0, key_no):

key = timelock(duration, ivs[i])

keys.append(key)

"""

This is where the magic happens: stitch the keys together

into one long chain of serial keys.

"""

en_ivs = []

en_rsa_priv_keys = []

rsa_public_keys = []

for i in range(1, key_no):

#Stitch keys together.

aes_cipher = make_aes_cipher(keys[i])

en_iv = encrypt(ivs[i], aes_cipher)

en_ivs.append(en_iv)

"""

We also encrypt an RSA key at this point in the chain,

that way people can use public key crypto to time-lock encrypt an

arbitrary number of plaintexts without recomputing work.

"""

random_generator = Random.new().read

rsa_key = RSA.generate(1024 * 2, random_generator)

rsa_priv_key = rsa_key.exportKey('DER')

en_rsa_priv_key = encrypt(rsa_priv_key, aes_cipher)

rsa_public_key = rsa_key.publickey().exportKey('DER')

en_rsa_priv_keys.append(en_rsa_priv_key)

rsa_public_keys.append(rsa_public_key)

#When should the timechain be released?

genesis_time = time.time() + (10 * 60)

#Generate timechain.

timechain = []

for i in range(0, key_no - 1):

link = {

"en_iv": en_ivs[i],

"en_rsa_priv_key": en_rsa_priv_keys[i],

"rsa_public_key": rsa_public_keys[i],

"expiry": genesis_time + ((i + 1) * duration)

}

timechain.append(link)

#Timechain starts here.

genesis = ivs[0]

#Publish timechain - not coded - for example only.

publish_timechain(genesis, timechain, genesis_time)

There’s a lot going on here so lets take a closer look.

Remember how we started with an IV and repeatedly hashed it to produce a time-locked key? Well in the parallel form that process is done hundreds of times simultaneously on different processors and at the end the IVs used for the keys are encrypted with a previous key so now the IVs have to be hashed sequentially before the next IV can be decrypted.

Dotted lines denote information being used as keys for ciphers and green denotes publicaly released information.

By building a chain of N minute time-lock encrypted, RSA public keys in parallel, and then stitching them together with symmetric encryption - it is possible to encrypt information in such a way that it can be released at arbitrary points in the future without depending on a third-party.

While this concept alone might be sufficient to solve a number of complex trust problems it is currently missing an important feature that the blockchain provides: an incentive. What mechanism is there for the the keys to be released after they’re solved? What mechanism is there to encourage participants to attempt to decrypt the timechain at all?

In the next section we propose a novel decentralized autonomous company that addresses these issues and more.

The timechain DAC[edit | edit source]

The timechain DAC adapts the basic idea behind the timechain but adds financial incentive so that participants not only want to decrypt the timechain but that doing so simultaneously forces individuals to release the RSA private key of the current link plus the IV to the next key.

Gwern Branwen and Peter Todd have already done work on using Bitcoin to incentivize the release of time-lock encryption keys but where my work differs from their own is in the way I’ve used the concept to create a general purpose, decentralized, time-lock encryption service that pays its participants to decrypts itself and forces them to provide the service.

How it works is … complicated

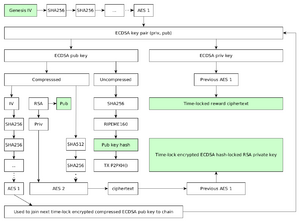

The DAC needs to be able to pay participants for their time so we’re going to need to insert ECDSA key pairs into the chain links. The ECDSA key pairs can be used to pay participants to break the timechain by allowing cryptocurrencies to be redeemed by signing with a particular key pair so the first person to break a link will get the coins.

Before we go into the full details its important to understand the game theory taking place here: because the first person who breaks a link is racing against countless other participants they must broadcast a redeeming transaction as early as possible or risk losing their reward. Thus, the timechain forces participants to redeem coins as early as possible.

Using these basic properties together with a special hash-locked contract it is possible to force participants to simultaneously release the details to decrypt the time-lock encrypted … AES encrypted … RSA private key and provide participants with the next IV in the chain.

This is done by using the public key of a time-lock encrypted ECDSA key pair as an IV. The public key is also used as a symmetric AES key to encrypt the RSA key pair. Finally, a hash of the public key along with the AES ciphertext for the RSA key is publicly released. The hash allows participants to pay fees to the DAC and requires providing the public key to redeem those coins (which simultaneously releases the secret key needed to decrypt the RSA key and gives participants the next IV in the chain.)

I think we’re going to need some code and diagrams over here …

import time

from Crypto.Cipher import AES

from Crypto import Random

from Crypto.Cipher import PKCS1_OAEP

from Crypto.PublicKey import RSA

import ecdsa

import hashlib

import bitcoin.base58

from bitcoin import SelectParams

from bitcoin.core import b2x, lx, x, COIN, COutPoint, CTxOut

from bitcoin.core import CTxIn, CTransaction, Hash160, Serializable, str_money_value

import binascii

def compress_public_key(public_key):

#https://bitcointalk.org/index.php?topic=644919.0

public_key = binascii.hexlify(public_key).decode("utf-8")

#Is there a prefix byte?

if len(public_key) == 128:

offset = 0

else:

offset = 2

#Extract X from X, Y public key.

x = int(public_key[offset:64 + offset], 16)

y = int(public_key[65 + offset:], 16)

if y % 2:

prefix = "03"

else:

prefix = "02"

#Return compressed public key.

ret = prefix + "{0:0{1}x}".format(x, 64)

return binascii.unhexlify(ret)

def make_aes_cipher(key):

return AES.new(key, AES.MODE_CFB)

def encrypt(plaintext, cipher):

return cipher.encrypt(plaintext)

def timelock(duration, iv):

#Starting time.

last_run = time.time()

#Generate time-lock encryption key.

elapsed = int(time.time() - last_run)

key = hashlib.sha256(iv).digest()

while elapsed < duration:

key = hashlib.sha256(key).digest()

elapsed = int(time.time() - last_run)

#Time-lock encrypted key.

return key

#For demonstration only.

def publish_timechain(genesis, timechain, genesis_time):

return None

"""

Generate starting IVs for parallel keys.

These need to be distributed to individual processors.

"""

ivs = []

key_no = 2

for i in range(0, key_no):

iv = ecdsa.SigningKey.generate(curve=ecdsa.SECP256k1)

ivs.append(iv)

"""

Generate individual time-locked keys.

(Image this is done in parallel because I'm lazy.)

"""

keys = []

duration = 10

for i in range(0, key_no):

verify_key = ivs[i].get_verifying_key()

ecdsa_pub_key = compress_public_key(verify_key.to_string())

key = timelock(duration, ecdsa_pub_key)

keys.append(key)

"""

This is where the magic happens: stitch the keys together

into one long chain of serial keys.

time lock -> ecdsa priv key -> btc tx -> ecdsa pub key -> (rsa priv + IV)

time lock -> ... -> timechain

"""

pub_key_hashes = []

en_rsa_priv_keys = []

rsa_public_keys = []

en_ecdsa_priv_keys = []

for i in range(1, key_no):

#Generate pub key hash - this is where we pay.

verify_key = ivs[i].get_verifying_key()

ecdsa_pub_key = verify_key.to_string()

pub_key_hash = hashlib.sha256(ecdsa_pub_key).digest()

pub_key_hash = hashlib.new('ripemd160', pub_key_hash).hexdigest()

pub_key_hashes.append(pub_key_hash)

#Build asymmetric, time-locked RSA key.

random_generator = Random.new().read

rsa_key = RSA.generate(1024 * 2, random_generator)

rsa_priv_key = rsa_key.exportKey('DER')

rsa_public_key = rsa_key.publickey().exportKey('DER')

rsa_public_keys.append(rsa_public_key)

#Encrypt RSA key with hash-locked AES key.

ecdsa_32_bytes = compress_public_key(ecdsa_pub_key)

ecdsa_32_bytes = hashlib.sha512(ecdsa_32_bytes).digest()

ecdsa_32_bytes = hashlib.sha256(ecdsa_32_bytes).digest()

hash_locked_aes = make_aes_cipher(ecdsa_32_bytes)

en_rsa_priv_key = encrypt(rsa_priv_key, hash_locked_aes)

en_rsa_priv_keys.append(en_rsa_priv_key)

#Stitch keys together with time-lock encryption.

ecdsa_priv_key = ivs[i].to_string()

time_locked_aes = make_aes_cipher(keys[i])

en_ecdsa_priv = encrypt(ecdsa_priv_key, time_locked_aes)

en_ecdsa_priv_keys.append(en_ecdsa_priv)

#When should the timechain be released?

genesis_time = time.time() + (10 * 60)

#Generate timechain.

timechain = []

for i in range(0, key_no - 1):

link = {

"en_ecdsa_priv_keys": en_ecdsa_priv_keys[i],

"pub_key_hashes": pub_key_hashes[i],

"en_rsa_priv_key": en_rsa_priv_keys[i],

"rsa_public_key": rsa_public_keys[i],

"expiry": genesis_time + ((i + 1) * duration)

}

timechain.append(link)

#Timechain starts here.

genesis = compress_public_key(ivs[0].get_verifying_key().to_string())

#Publish timechain - not coded - for example only.

publish_timechain(genesis, timechain, genesis_time)

If you read the code very closely you will notice that I’m using compressed ECDSA public keys as IVs. The reason for that is that Bitcoin-style ECDSA public key hashes are released publicly to everyone in the form ripemd160(sha256(uncompressed_ecdsa_pub_key)). If a vulnerability were to be found in ripemd160 that could lead to inverted hashes and I was using the same input data (uncompressed ECDSA public keys for the IVs), then sha256 hashing the inverted ripemd160 hash would essentially yield arbitrary points on the timechain: extremely bad.

By using compressed keys for the IVs we rely on the avalanche effect of cryptographic hash functions which states that any small changes to the input data produce profoundly different hashes (so even if ripemd160 was completely invertible it would not effect the security of the timechain.) For the same reason, different hashes of compressed ECDSA pub keys are used as symmetric AES keys to encrypt the time-locked RSA key.

The dotted lines in the diagram mean that the input is being used directly as the key to the cipher (not that the cipher is being applied to the input.) Green boxes denote publicly available information.

Another way to conceptualize the Timechain DAC is listed bellow.

Genesis IV -> sha256 -> … -> sha256 -> AES1 -> (next ECDSA priv key, AES2(new RSA priv key))

compressed ECDSA pub key -> iv - > sha256 -> … -> sha256 -> AES1 -> (next ECDSA priv key, AES2(new RSA priv key))

compressed ECDSA pub key -> iv -> sha256 -> … -> sha256 -> AES1 -> (next ECDSA priv key, AES2(new RSA priv key))

…

Timechain DAC.

Redeeming funds from the timechain DAC[edit | edit source]

After winning the race to generate a new time-lock encrypted AES key and gaining access to an ECDSA private key with funds inside it - you want to spend them as early as possible. This can be accomplished with a standard Bitcoin transaction type called a “pay to public key hash”.

P2PKH was invented as a way to have shorter Bitcoin addresses and to conceal the owner of a public key in the event that a flaw was found in ECDSA but for our purposes it allows us to create complex contracts that tie directly into the timechain.

The Bitcoin transaction Script to fund a P2PKH transaction looks like this:

OP_DUP, OP_HASH160, ripemd160(sha256(ecdsa_public key))

… which is the same public key hash generated previously. To redeem the transaction simply provide the original public key and a valid signature.

Solving complex trust problems with the timechain[edit | edit source]

So … ah this is the section where we show you how to build unhackable Bitcoin services. It’s been quite a ride to get here but so far I’ve showed you how time-lock encryption works; How to generate keys in parallel; And how to use game theory principles to incentivise cooperation by creating the first DAC based on time-lock encryption.

Now let me show you why this is important.

Example 1: unhackable cryptocurrency exchange

There’s several excellent ways to build an unhackable exchange using the timechain but probably the best way is to adapt Uptrenda style p2p smart contracts to reduce the need for an active dispute system.

In practice the exchange would use the timechain to build a chain of ECDSA private keys locked at 5 minute intervals and then publish the public keys without holding on to the original private keys. The public keys could then be used by smart contracts to ensure the owner would eventually gain back full control over their coins if the contract was interrupted.

3, Owner, Owner, Recipient, Timelock, 4, OP_CHECKMULTISIG

In the multi-sig example we used a single timechain to demonstrate the concept but the possibilities here are endless. You could increase the owner’s leverage to 3 keys and change the multi-sig to 4 of 6 which would leave room for an extra time-locked key on a different timechain and since the owner’s leverage is disproportionate: gaining access to the other keys doesn’t give an attacker enough leverage to steal coins.

What about threshold ECDSA If a company were to act as a trusted dealer for ECDSA secret shares - the shares could be distributed to multiple timechains. This would allow for representing extremely complex trust relationships that could easily scale to an arbitrary number of participants. The advantage of this approach is you wouldn’t have to use multiple keys for the multi-signature construction which in Bitcoin is quite limited.

Example 2: more reliable escrow services

Most escrow services rely on primitive trust relationships. A good example of this is the common 2 of 3 scheme where 2 keys are required to sign a transaction. The multi-signature address typically looks like this:

2, Owner, Recipient, Company, 3, OP_CHECKMULTISIG

The idea is that if the company disappears the owner can collaborate with the recipient to negotiate a refund. Unfortunately, this relies on the assumption that the recipient will cooperate and a reliable financial system based on smart contracts needs to assume the presence of irrational actors (because people like to mess shit up just because they can.)

A simple fix is to time-lock the company key so the extortion scenario doesn’t occur. To make the process slightly more secure you could use a distributed network of oracles in a 9 of 15 scheme together with a reputation system and encrypt the signing keys with the timechain.

Example 3: unhackable smart contracts

Smart contracts can pay a small fee to the timechain to help incentivise participants to provide a reliable time-locking service and then use the resulting service to time-lock a chain of ECDSA private keys.

The ECDSA private keys can then be used in place of nLockTimed refund transactions used by micro-payment channels and atomic cross-chain transfers by allowing time-released leverage to return back to the owner.

3, Owner, Owner, Recipient, Timelock, 4, OP_CHECKMULTISIG

This would solve the transaction malleability problem in refund protocols which enables an attacker to invalidate the refund by changing the TXID of the transaction that the refund spends from before its confirmed in the blockchain - a flaw leading to a possible extortion scenario.

Example 4: more reliable multi-signature wallets

If the owner stores their coins in a multi-signature wallet and stores some of the keys offline, it is much more difficult for an attacker to steal coins but the problem is in keeping a reliable backup in the event of failure.

One possible solution is to use the timechain. If the owner encrypts a portion of their keys on the timechain the resulting ciphertext can be given to a third-party to hold (or stored on a decentralized database) without the third-party having access to the keys.

Example 5: Unhackable timed matrix wallets

Timed matrix wallets (TMWs) adapt the idea behind the timechain to improve the security of coin storage by storing coins over time. The idea is that the leverage required to spend a subset of coins is released over time, thereby giving the owner the opportunity to deal with any intrusions before the attacker has a chance to spend the coins.

TMWs are based on the following assumptions: - Payments don’t need to be made straight away. - Coins don’t need to be available all of the time. - Users don’t need access to all of their coins for any given payment. - And: attackers need to be able to move coins quickly.

To take advantage of these properties, TMWs split funds up into a number of multi-sig accounts where a portion of the keys are made to be published in the future via the timechain. The user then deletes their copy of the ECDSA private key but before they do: they also create a new transaction (stored offline) which can be used to shuffle the coins into a future time slot in the event of an intrusion.

Now, if an attacker gains access to the user’s private keys the entire portion of their funds is never at risk and the attacker has to wait to spend coins which can be easily cancelled and moved to a new set of private keys by using the refund transaction. Payments under this scheme must therefore be scheduled into an appropriate time slot, with any unused coins sliding into a future time slot over an infinite period.

This process is kind of analogous to being able to thaw out a cold wallet when its needed and putting it back into deep freeze automatically when it’s not - a process that would explicitly bias the average attacker who needs to be able to move coins out quickly or risk being discovered.

Example 6: all the usual stuff time-locked crypto allows

The timechain would act as an excellent dead man’s switch for journalists or politically exposed individuals; It could be used for voting or auctions; Or simply for reliable data decryption / backups.

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

In this article we have described a system for solving the transaction malleability problem in smart contract protocols by introducing the timechain.

The timechain is a new deterministic data structure that uses a chain of time-lock encrypted RSA public keys at 5 minute intervals whose publication is incentivised through the use of hash-locked financial rewards.

Financial rewards are claimed by breaking links in the chain which must be done as early as possible or risk losing the reward. When financial rewards are claimed, the RSA private key is released automatically allowing anyone to decrypt time-locked information using that key.

The resulting process forms a decentralized autonomous corporation (DAC) that rewards participants for providing a reliable time-lock service and can be “hired” by smart contracts to provide a secure refund system without having to rely on malleable refunds transactions or a third-party service.

Finally, the timechain also makes it possible to improve the security of a number of services that handle cryptocurrencies including wallets, escrow agents, and currency exchanges by removing the need for centralization of ECDSA private keys.

Frequently asked questions & answers[edit | edit source]

How do you avoid biasing the reward for the first participant?

The first person who starts breaking the timechain will have an unnatural lead on everyone else making it extremely improbable that anyone else will be able to claim the reward. To solve this problem we borrow an idea from Bitcoin mining called a nonce.

Instead of using a full compressed ECDSA public key for the IVs, we remove some of the bits and replace them with random data and use the modified ECDSA public key as the IV. How much information to remove depends on how early in the chain the link occurs. If the link occurs at the start then only a few bits are removed but if the link occurs late in the chain, then many more bits may be removed to account for hardware getting faster and more computing power being used to find the correct IV.

The new non-deterministic IV is then hashed with Scrypt and encrypted with the RSA public key of the previous link. Now, when a solution is found it also publishes a hash of the next IV in the chain which tells participants what the first IV should hash to (which they don’t yet have.)

Therefore, the first person to break a link has no further advantage in breaking the next link as the next IV must be brute forced using a simple nonce-based puzzle before the link can be broken.

What if there is no reward? Why bother?

We propose adding a blockchain and cryptocurrency to the system, but with slightly modified coinbase. Every time a link is broken, the entity that broke it can add a new block to the blockchain and give themself a fixed amount of the timechain’s currency (Time.)

To be able to claim Time a proof of broken link is required which is simply a receiving address and public key of the next IV signed with the ECDSA private key of a previously unbroken link plus any pending Time transactions. When nodes in the network receive this information they issue Time to the receiving address and confirm any pending transactions.

Transactions are handled the same for this as they are with Bitcoin: with new blocks on the blockchain being used to process transactions and assign any fees to the miner. The only fundamental difference is in mining process where hash rate is used to secure the overall integrity of the blockchain by miners in exchange for a small amount of Time.

What about improvements to SHA256 hash speed?

In practice the rate at which the timechain is broken will differ from the exact time needed to produce it. If there is a significant advance in hardware that allows for faster serial generation of SHA256 hashes the timechain will be broken faster. On the other hand: if there is a lack of participation in the cracking or solutions to the IV puzzle aren’t found fast enough - the timechain will be broken slower than expected.

The solution is to adjust the way we use the timechain based on the cracking time for the previous link (clockskew.) That way, the timechain itself does not need to be adjusted and the structure stays secure even in the face of hardware advances.

Clockskew over time can be used to further inform the construction of future yearly timechains allowing the difficulty of the IV puzzle to increase based on the time increases seen in cracking the previous year’s timechain.

But … you have to trust the timechain, right?

Yes, but if you’re worried about the integrity of the timechain you can always use multiple timechains. One way to go about this is to use the “threshold time-lock encryption” technique described in the Uptrenda white paper.

If you’re using smart contracts multi-sig also allows you to make some of the keys redundant so if there’s multiple timechains protecting your contract, some of the timechains can fail without loss of funds.

And well … you can always generate your own timechain.

The most important thing to remember is that the timechain provides a passive function with no intervention necessary so even if companies only use this technology to remove the need to hold private keys in some cases - that is still a huge improvement in security for the services that use this - in particular services based on smart contracts and DACs.

How will you handle consensus?

Participants in the timechain will download software compiled with the timechain precomputed. The timechain will allow them to verify whether peers have found a solution allowing nodes to advance further along the chain. It will probably be necessary to use a peer-to-peer network to share solutions and add fault tolerance so that nodes can easily broadcast solutions to see current progress made in breaking the chain.

This open style of participation would also make it harder for a centralized service to lie about the progress made in breaking the chain thereby improving the reliability of time-locking.

Users of the timechain will therefore have accurate information on where in the chain to encrypt data in order to achieve a desired time-lock taking into account the time field includes in blocks and the clockskew - which is a measure of the current rate of cracking against the expected time to break the chain.

Towards a prototype for the first timechain

A prototype / test version of the timechain can be created on a single GPU so long as the generation of the chain can outpace the rate of cracking. Furthermore, if the RSA keys are generated in advance then the keys can be used to time-lock information before the timechain has been generated up to that point. This would be analogous to laying tracks for a railway leading up to new terminals while a very slow train was not far behind you.

Obviously this structure would not be used for a production system since it means keeping the computer responsible for generating the timechain online and requiring it to keep RSA keys around which would opens it up to the very same problems the timechain is suppose to solve - but … the concept can still be used to show people how the timechain works for a relatively low cost without having to rent out a GPU cluster to do it.

Thoughts?